Apple is really making Qualcomm and Windows on Arm look bad

I’m a Windows on Arm fan. In fact, I’m a Windows fan. I’ve spent the bulk of my career writing about Windows, Microsoft, laptops, and the whole ecosystem. When Qualcomm and Microsoft announced Windows on Arm in 2016 with actual x86 emulation, I was excited. I wasn’t excited because of the benefits that Arm processors promised.

It was the nerdy side of me that was geeking out over it. It was Windows on a new processor architecture, in a way that might actually work! While the early days of Windows had no shortage of CPU architectures that it supported, by the time Windows 10 rolled around, it was just AMD64, or x64.

XDA-Developers VIDEO OF THE DAYQualcomm promised things like amazing battery life, integrated cellular connectivity, and instant wake. There were only a few partners at first, but that grew over time to pretty much everyone except for Dell.

Then, Apple joined the pack. The company announced that it would transition its Mac lineup to Apple Silicon in June 2020, which is less than two years prior to this writing. And since then, it’s made some breakthroughs in the PC space that remain unmatched by Windows. And given that Qualcomm has over five years of trial and error in the space, Apple is really making Windows on Arm look bad.

A brief history of Windows on Arm

Windows has been running on Arm processors for a long time now, at least in some form or another. Obviously, Windows Phone ran on Arm chips, and that paved the way for a lot of what we see today. Windows Phone 7 ran on a Windows CE kernel with Silverlight apps, and that was all replaced in Windows Phone 8, which used the Windows NT kernel. Not a single Windows Phone 7 device was upgraded to Windows Phone 8, despite flagships like the Nokia Lumia 900 being released just a few months before.

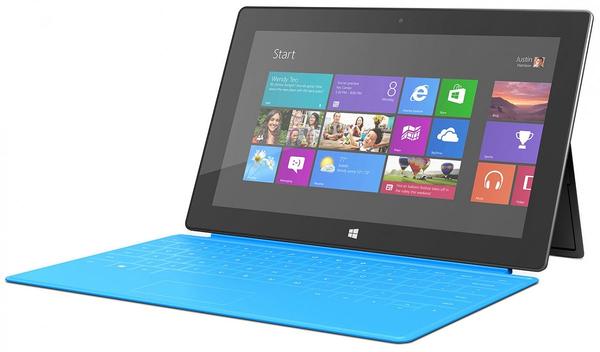

Alongside Windows Phone 8 came Windows RT (and Windows 8, for that matter), the first attempt to get proper Windows running on an Arm processor. At the time, the big partner was NVIDIA with its Tegra processors, which were found in the Surface RT and Surface 2. Nokia had a Snapdragon 800 device with the Lumia 2520 though.

Surface RT

Windows RT was a horrible failure. Despite looking identical to Windows 8, it could only run apps that came from the Windows Store, making it confusing for customers downloading apps from the web that said they run on Windows 7 and higher. It didn’t help that even Windows 8 was one of the most poorly received versions of Windows in history, thanks to its radically redesigned UI. Microsoft ended up taking a $900 million hit on Surface RT tablets that it simply couldn’t sell, or had to massively discount. Despite that, Surface 2 was still released.

When Windows 10 was announced in 2015, it was confirmed that Windows RT devices would not receive it. Those users instead got Windows RT 8.1 Update 3, which offered a return of the Start Menu, and not much else; certainly not a Windows 10 kernel or the Universal Windows Platform.

In December 2016 at Snapdragon Technology Summit in New York, Qualcomm and Microsoft announced their newest attempt at Windows on an Arm processor. The key difference was x86 emulation. Ideally, the user wouldn’t even know the difference between the ARM64 and AMD64 versions of Windows 10. Obviously, x86 emulation meant no 64-bit emulation, something that Microsoft said at the time that it wouldn’t do. Most apps had 32-bit variants, and the hope was that app developers would convert their apps to run natively anyway.

Lenovo Miix 630

Fast forward a year to December 2017, when Snapdragon Summit was moved to Maui in Hawaii. This was when the first two ARM64 PCs were shown off for journalists. They were the ASUS NovaGo and HP Envy x2, while Lenovo had the Miix 630 coming later. They used Snapdragon 835 chipsets, which were slightly modified versions of the mobile processors of the same name.

The Snapdragon 850 was announced a bit later, and that was based on the Snapdragon 845 chipset. Once again, there were only a handful of laptops and tablets that used it, such as Samsung’s Galaxy Book 2 (not to be confused with the Samsung Galaxy Book 2 that was just released), the Lenovo Yoga C630, and the China-exclusive Huawei MateBook E. Some others joined the pack later on.

But those others joined after Qualcomm announced its first chipset that was built from the ground up for PCs, the Snapdragon 8cx. It was launched at Snapdragon Summit in 2018. The ‘c’ stands for compute, and the ‘x’ means extreme. Devices to use this include the Lenovo Flex 5G, the Samsung Galaxy Book S, and the Microsoft Surface Pro X (the chipset was slightly modified and rebranded as the Microsoft SQ1).

Unfortunately, it took a while for the Snapdragon 8cx to ship. At Snapdragon Summit in 2019, Qualcomm introduced the Snapdragon 8c and 7c, and vanilla Snapdragon 8cx devices still hadn’t shipped. To decrease the time to shipment, the Snapdragon 8cx Gen 2 barely had any changes at all.

In December of last year, Qualcomm announced the Snapdragon 8cx Gen 3, a proper refresh of the chip. It’s promising big performance gains, but it’s still not going to keep pace with Apple’s M1. That’s going to start being seeded to OEMs in the second half of this year, thanks to the company’s Nuvia acquisition that will give it the chops to make custom Arm silicon.

Another big thing that happened last year was that Windows 11 was released, bringing 64-bit app emulation to Arm. We’ll talk more about that in a bit though.

Qualcomm hasn’t delivered on its promises

There were three main promises that Qualcomm promises with Windows on Arm. The first was stellar battery life. Arm chips use a big.LITTLE architecture, with powerful cores for tasks that require it, and efficiency cores for everything else. Not only was this supposed to result in battery battery life, but it allowed PCs to instantly wake, similar to how your phone does.

The third promise was integrated cellular connectivity. Qualcomm’s chipsets have integrated cellular modems, so for the first time, 5G (4G LTE at the time) would be standard for a product, rather than an expensive premium like it is with Intel laptops.

The most glaring problem is that the battery life we were promised isn’t showing up in real-world usage. Sure, with the new processor architecture being more efficient, a lot of laptops are fitting into slimmer designs, meaning that they have smaller batteries. Still, this isn’t the situation where we can leave our chargers at home like we were promised.

Microsoft Surface Pro X

I’ve personally reviewed almost every Windows on Arm laptop that’s ever been produced, from every generation of processors, and I can tell you this: with the exception of the Lenovo Flex 5G, I have never included battery life as a plus for the device. With a Surface Pro X, battery life is no different from its Intel-powered sibling.

Integrated cellular connectivity hasn’t turned out to be what was promised either. Almost every Windows on Arm laptop that ships today has a Wi-Fi only base model, so even in 2022, you still have to go through the hassle of hot spotting your phone to connect to the internet on the go.

The problem is that the experience has been mostly underwhelming. Devices have been way more expensive than you’d expect for what they offer, especially in the early days of the Snapdragon 835 and Snapdragon 850. Also in the early days, performance just wasn’t there. It was easy to look at the Snapdragon 835 as just a starting point, but now that we’re five years in, I think we expected this to be better.

Samsung Galaxy Book Go

I don’t want to bash Qualcomm here, because I love Windows on Arm laptops. The Samsung Galaxy Book Go comes in at an entry-level price point, and it weighs only three pounds. That’s unheard of at that price, and it’s something that’s unlocked by using an Arm processor. The Lenovo Flex 5G was the first 5G laptop to use Sub6 and mmWave, and indeed, every laptop that supports both has an Arm processor. Speaking of Qualcomm wins, even the Intel-powered 5G laptops on the market almost all have Qualcomm modems.

The Samsung Galaxy Book S was pretty wild too. It was so thin and light with its fanless design that I considered it something that it was a form factor that could only be achieved with an Arm processor. It did ship with an Intel Lakefield chip at one point, but that wasn’t any good; Lakefield was Intel’s first attempt at a hybrid chip.

Apple is the one delivering new experiences now

Apple switching its entire Mac lineup away from Intel is a big deal. At the time of this writing, there are only two Intel Macs still being sold by the firm: the Mac Pro and certain configurations of the Mac Mini.

The Cupertino firm delivered an experience that Microsoft hadn’t been able to offer before Apple Silicon Macs even shipped. It offered seamless running of all apps that were built for Intel-based PCs. In fact, Macs don’t even support 32-bit apps of any kind, so all Apple built was 64-bit emulation. Side note: you might recall that before the M1 processor shipped in a product, Apple had a developer kit that used the iPad Pro’s latest chipset, so that’s when new features like this shipped.

Apple’s solution is called Rosetta 2. The first time you go to install an x64 app, you’ll be prompted to install Rosetta 2, and you’ll never have to think about it again. You won’t notice any performance issues either.

Apple beat Microsoft to the punch here. Microsoft announced 64-bit emulation for Windows on Arm in September 2020, three months after Apple. As I mentioned earlier, the official word back in 2016 was that Windows on Arm would never have x64 emulation. I can tell you that that changed by late 2019, as I reported at the time. In other words, this was in the pipeline long before Apple announced, but Apple got there first.

Then, Apple released a product. I wasn’t too excited about the M1 in its original three products, which were the MacBook Air, the 13-inch MacBook Pro, and the Mac Mini. It only supported one external monitor, which is unacceptable for something with the word ‘Pro’ on it. Moreover, performance was good, as was battery life, but it wasn’t blowing away what Intel was offering in any way.

24-inch iMac

It was when new form factors started to ship that things got interesting. Apple released the 24-inch iMac with an M1 chip. Not only was it unnaturally thin, but the company was using the same processor in devices from the 11-inch iPad Pro to a 24-inch desktop PC. This is the first time it was really worth pointing out that Qualcomm and Microsoft aren’t doing what Apple is. Qualcomm isn’t aiming at all-in-one PCs, or even the best performance. It’s always aimed at super thin and light, premium experiences.

16-inch MacBook Pro

Then came the MacBook Pro and the introduction of the M1 Pro and M1 Max chipsets. As a Windows fan, it legitimately upsets me that these things are so good. Once again, it’s really not about performance. But the performance is on par with an Intel machine with dedicated graphics, and battery life is phenomenal. If I hit the road with a laptop that has that kind of power, I’m definitely bringing a charger. I don’t have to with the MacBook Pro; at this point, it’s also worth remembering that that was one of Qualcomm’s big promises.

Not only that, but it allowed Apple to put the same internals in the 14-inch and the 16-inch models for the first time. Previously, the 13-inch MacBook Pro used a U-series chip with integrated graphics, while the 16-inch model got the 45W processor and dedicated graphics, because it had the space to do it.

Again, this isn’t something that Qualcomm is currently aiming for. I asked years ago if it had any plans of expanding beyond competing with Intel U-series, and I was flat-out told no. That could have changed of course, since Apple is doing it. But that makes it just another example of how Apple is the one setting the trends in the Arm computing space now.

Apple Studio display and Mac Studio

If that’s not enough, Apple just launched the Mac Studio and its new M1 Ultra chipset. Using a process called UltraFusion, it basically glued two M1 Max chipsets together, something that you can do when you design the chip. Apple compared M1 Ultra performance to a high-end Intel PC with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPU.

The big difference between the Mac Studio and such an Intel-powered PC, of course, is that the Mac Studio is just 3.7 inches tall and the footprint is a 7.7×7.7-inch square. Just for reference, you won’t even find an RTX 3090 that’s less than 12 inches in length, let alone a computer that has the thermals necessary to use it.

Again, this really isn’t about performance on its own. It’s about bringing that performance without making the compromises Intel needs to make to get there. That’s what makes Apple Silicon so interesting.

Qualcomm needs to step it up, and it probably will

First of all, I’m really looking forward to the Lenovo ThinkPad X13s, the first device to use the Qualcomm Snapdragon 8cx Gen 3. I got to use the Snapdragon 8cx Gen 3 Reference Design for a couple of days at Snapdragon Summit, and I was really impressed with it. Putting that in a laptop with the kind of build quality that ThinkPad offers is exciting.

Snapdragon 8cx Reference Design

It’s not setting the bar for Arm computing though. Apple is doing that, and I don’t think that anyone can deny it at this point.

Qualcomm is working hard on its own custom silicon though, and that’s when things are going to get really interesting. Thanks to its Nuvia acquisition, it’s going to be sampling to OEMs later this year. It’s got some catching up to do, but this should give Qualcomm the tools it needs to compete with Apple.

It’s also going to be exciting with other chip vendors enter the Windows on Arm space, as MediaTek is planning to do when the exclusivity deal between Microsoft and Qualcomm expires. We might see other vendors as well.

But no matter how it does it, Qualcomm needs to step it up here. In 2016, it was ready to chip away at a market that’s dominated and built around Intel and AMD. It could afford to be that third chip-maker, climbing up one rung at a time. But now, Apple is showing what can really be done with Arm chips in PCs, and with its head start, Qualcomm is the one that should have been doing this.

}})