HyFlex Is Not the Future of Learning

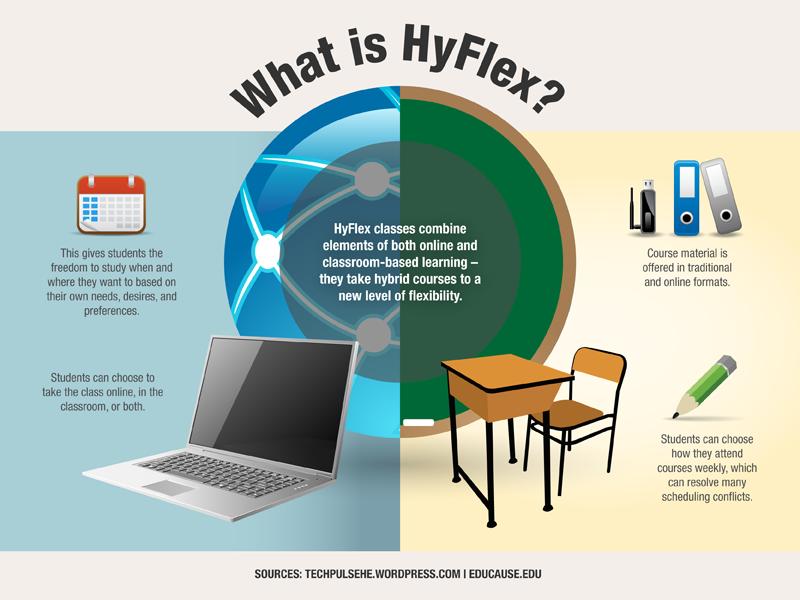

I was recently in a high-level meeting at my university where one of my colleagues gave a sober, heartfelt presentation on the challenges and lessons learned from HyFlex teaching last year. For those not in the inner circle of educational lingo, “HyFlex” is a portmanteau of hybrid and flexible—or it’s occasionally interpreted as highly flexible. For some the term is simply synonymous with the future.

HyFlex is meant to pithily describe a method of teaching some students in person, in a traditional classroom, while simultaneously teaching other students remotely via Zoom or other remote video-streaming apps. Often these two different groups of students might overlap or switch places throughout the term. It is a style of teaching that involves carefully choreographing cameras, speakers and microphones in addition to navigating the traditional layout of a classroom with students present. The instructor becomes a performer, an emcee and a technologist (often a clumsy one, at that).

HyFlex teaching effectively means teaching two iterations of the same class, simultaneously: 1) a version taught more or less the old-fashioned way, and 2) a version mediated and modulated to far-flung students whom the instructor may never meet in person.

Most Popular

One of the main takeaways from my colleague’s presentation was that it was simply exhausting: the learning curve, the accommodation of different students’ needs across the two platforms, the adjustment of curriculum and assignments to fit such a broad and shifting range of learners. Another more positive lesson learned was to trust students to get what they could, as they could, out of the classes—to ease off the regulatory and monitoring impulses, and to let the creation of knowledge happen more irregularly and individually.

To me, sitting a few seats away from my colleague during his presentation, the message was clear: while we had survived HyFlex education during the long duration of the pandemic, we wouldn’t wish it on anybody, as it posed so many challenges that inevitably interfered with the basic goals of mastering a subject. On campus, the consensus was pretty clear: everyone lost something in HyFlex courses. The students in class, the remote students and the instructor each felt they’d been given short shrift.

After my colleague’s presentation, however, a few members leading the steering committee began to wonder about increasing our HyFlex offerings. “It sounds like we can reach more students this way. Can we attract an even more diverse enrollment if we make more of our classes HyFlex? Isn’t this the future?”

In a moment when universities seem to operate on a grow-or-die calculus, anything to drive expansion or reach becomes tantalizing.

Some caveats were raised: even if we give all our students laptops, we cannot predict, much less control, whether or not they will have a stable internet connection. Furthermore, as many of us found out during our initial forays into Zoom learning, students’ living situations were equally variable—with very real implications. Some students had to join class from their cars or walking around their neighborhood if they didn’t have a private place in their homes where they could log in. The infamous black boxes in Zoom grids had real back stories. (It wasn’t just students being lazy.)

It occurred to me that whatever else the experience involves, whatever curricular intricacies and degree programs a student pursues, college is also a place. It gives students all sorts of sites and locations where learning can happen: library alcoves, dorm rooms, Adirondack chairs and picnic tables in the quad, dining areas and coffee shops. Of course, a student’s time on a campus isn’t all spent studying; such spaces also accommodate any number of social gatherings, spontaneous encounters, power naps and zoning out.

It’s the physical place of college that lets all this happen, suffusing and surrounding proper learning. And whatever HyFlex allowed us to do in getting through the pandemic—staying on track, completing coursework, finishing terms—we risk losing our bearings when it comes to not having the physical locus of higher education.

I felt this viscerally last semester, as my students and I attempted to regain a sense of normalcy: sitting together, reading texts aloud, commenting and questioning, articulating complex ideas. It all felt incredibly tentative, almost surreal. As one of my students described it, “It feels like a Black Mirror episode.” I took this to mean that while everything seemed normal, there were all these looming risk factors— a sense that campus life was on the verge of a shocking distortion. It was as if all the activity on campus could suddenly be revealed as a fragile performance—and we’d all be back on Zoom again, cobbling together our classes from afar. And in fact, to start the spring semester—with Omicron spreading aggressively—here we are back in the vague ontology of remote learning.

The “flex” in HyFlex is meant to suggest the flexibility that our technologies allow: the ability to join a class from home or the time-management options made possible through asynchronous instruction. The wish image is recorded lectures that can be absorbed at the most convenient time, quizzes and discussion boards that can take place organically and at the whims of self-motivated students, and a nimble instructor who can pop online and monitor learning progress … whenever.

The reality is something much darker. It means students and instructors alike seem to have endless tasks: a constant deluge of boxes to tick, videos to watch, assessments to mark. They pile up in the timeless void of the phone screen or the computer desktop. Midnight deadlines become an infinite regress. And while coursework would seem to be tidily organized under our learning management apps, in files and folders and subfolders, all of it pulls everyone involved further away from the college experience.

Don DeLillo’s 1985 classic postmodern (yes, we can use those terms together now) novel, White Noise, opens with what used to read as a brilliant parody of a small liberal arts campus at the beginning of the fall semester:

The station wagons arrived at noon, a long shining line that coursed through the west campus. In single file they eased around the orange I-beam sculpture and moved toward the dormitories. The roofs of the station wagons were loaded down with carefully secured suitcases full of light and heavy clothing; with boxes of blankets, boots and shoes, stationery and books, sheets, pillows, quilts; with rolled-up rugs and sleeping bags; with bicycles, skis, rucksacks, English and Western saddles, inflated rafts. As cars slowed to a crawl and stopped, students sprang out and raced to the rear doors to begin removing the objects inside; the stereo sets, radios, personal computers; small refrigerators and table ranges; the cartons of phonograph records and cassettes; the hairdryers and styling irons; the tennis rackets, soccer balls, hockey and lacrosse sticks, bows and arrows; the controlled substances, the birth control pills and devices; the junk food still in shopping bags—onion-and-garlic chips, nacho thins, peanut creme patties, Waffelos and Kabooms, fruit chews and toffee popcorn; the Dum-Dum pops, the Mystic mints.

It used to read as a parody; now it reads as an elegy. College isn’t such a place anymore. There’s barely a shared sense of coming together to learn. Rather, higher education is trumpeted as a grid of apps piped into everyone’s personal phones. Instructors are directed to “deliver” their lessons in discrete chunks and units. Each student gets a pathway to graduation—an “academic journey,” in the parlance, but an adventure detached from any real ground.

HyFlex is a synecdoche for this reality: a fantasy notion of the future of higher education that, in truth, is a haunted shell of itself.

}})